The chance for a new Bauhaus

Mart Stam did not pursue his utopia for founding a new Bauhaus in the constituent GDR alone.

In continuation of Hannes Meyer’s Bauhaus directorship of 1928-30 with the concept of people’s needs and collective work, several designers attempted to participate in socialist construction after the end of World War II. Particularly in areas of advertising, furniture production, and urban planning, attempts were made to combine political goals and the aesthetic ideals of modernism.

This was done primarily out of the hope that the socialist state would be oriented toward modernism. In the political and cultural-political power vacuum, attempts were made in many places to position the respective ideas. A struggle broke out among people who pursued similar political goals over the cultural-political orientation in the founding socialist state.

In Dresden, the communists Robert Siewert and Otto Falkenberg in particular played an active role in ensuring that the economic reconstruction and the rebuilding of the war-ravaged city succeeded through an orientation toward the principles and design ideals of modernism. In addition to Mart Stam, the two relied on Franz Ehrlich and Kurt Junghanns.

On connection of Liv Falkenberg and her common time with Mart Stam in the Dutch architectural group Opbouw Liv’s husband, Otto Flakenberg gets in touch with him. As Saxon Minister of Industry, he saw Mart Stam as an opportunity to both rebuild the war-torn city and reorganize the art schools.

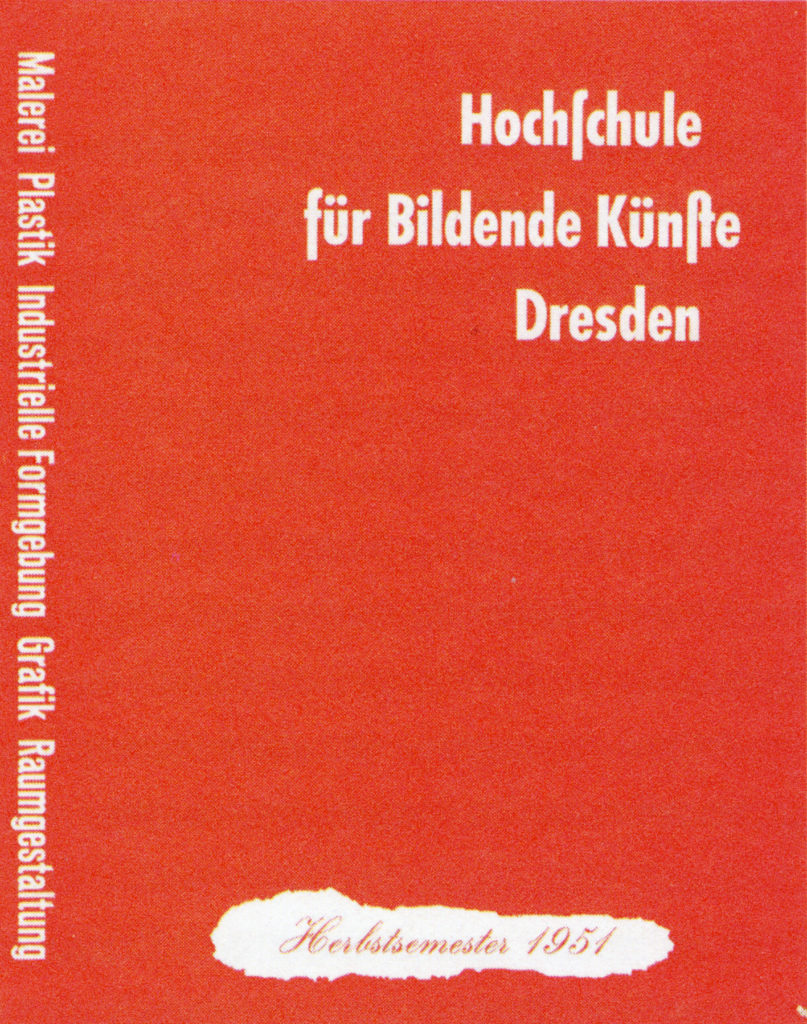

Stam came to Dresden in 1948 and began to create a Gesamtkunsthochschule by uniting the Hochschule für Werkkunst and the Akademie der Bildenden Künste, which, like the Bauhaus in Weimar in 1919, would combine art and craft or design. According to Stam’s proposal, this relationship should also be reflected in its name: BAUSCHULE staatliche hochschule für freie und industrielle gestaltung.

The growing importance of design since the founding of the Bauhaus, or rather its clearer outline, was reflected in the orientation of the Dresden school. Stam created a new faculty for industrial design, in which industrial designers were supposed to be trained in the fields of ceramics, metal, furniture as well as machines including automobiles. Falkenberg and Stam saw this as a crucial element in the economic development of production in the SBZ and later the GDR. As support, In addition Mart Stam wanted to employ Marianne Brandt and Hajo Rose, two Bauhäusler, as lecturers.

Stam’s design of the “Dresden Bauhaus” was threatened from two sides. On the one hand, it hit right in the middle of the discourse about the right “form” of art under socialism. On the other hand, the battle over the concept of art between fine art and design was being waged in Dresden in particular. Stam came as the successor to the painter Hans Grundig. The leadership of an art academy as an architect was perceived by many Dresden painters and visual artists as a harsh affront and led to violent reactions. Between these two fronts, the idea of a new Bauhaus by Stam, the Falkenbergs, Siewert, Brandt and Rose could not stand.

An end point of the discourse was the resolution Against Formalism in Art and Literature, for a Progressive German Art passed by the Central Committee of the SED in 1951. Already one year before Stam had to leave Dresden, the faculty of industrial design closed directly. He was transferred to Berlin to the Weißensee School of Art.