School of Casablanca

In 2020, KW Institute for Contemporary Art and Sharjah Art Foundation, in collaboration with Goethe-Institut Marokko, ThinkArt and Zamân Books & Curating, initiated the collaborative project School of Casablanca. Their goal is to revisit the ideas and actions of the Casablanca School between the years of 1964 -1968, which culminated in the avant-garde activist magazine Souffles. The initiative will continue through 2024.

Many instances of experimental creative research exist in Morocco and resemble the spirit of the Casablanca School. Among them, underground and multidisciplinary Khial Nkhel or the women-led, French-Moroccan Calypso3621 as rising artist nomadic collectives. Norseen Collective and Kimia Collective as examples of media and photographic experimentation. Le 18, Derb el Ferrane in Marrakech with initiatives such as Qanat on the history and politics of water, Maison de l’Oralité in Aït Ben Haddou, or the project Casamémoire as centres exploring Moroccan collective identity. Think Tanger, a cultural platform of urban challenges arising in Tangier, contemporary art centre Mahala Art Space, or La Fabrique Culturelle des Anciens Abattoirs de Casablanca, are concerned with territory & locality. The Biennale of the Mediterranean art schools being organised in the School of Fine Arts of Tetuan this year is another example of Northern Morocco’s influence in the Mediterranean.

Looking at Moroccan art, I see a history fraught with gaps, nonsensical dead-ends, unsaids and nebulous chronologies, which is common to any colonial and neo-colonial histories after all. The French protectorate acted as a jammer, scrambling Morocco’s sense of collective identity. When doing research, I’ve had many people ask me:

Is it possible to make a whole today, to disentangle Moroccan identity from outside influence? To me, this question should mirror an even more controversial one: is it possible to separate European identity from its colonial oppression?

Balkahia, Melehi, and Chabâa had all lived in Europe to continue their fine arts studies. Bert Flint was Dutch. Toni Maraini, Italian. From a collective identity perspective, it would remain a detail if we were to look at a Dutch painter studying in France or a French one travelling to Algeria for inspiration. But to build an understanding of Moroccan art, it is absolutely crucial. Because what is at play, what is at heart, is the very existence of a Moroccan (fine) art history, of a clear Moroccan artistic voice.

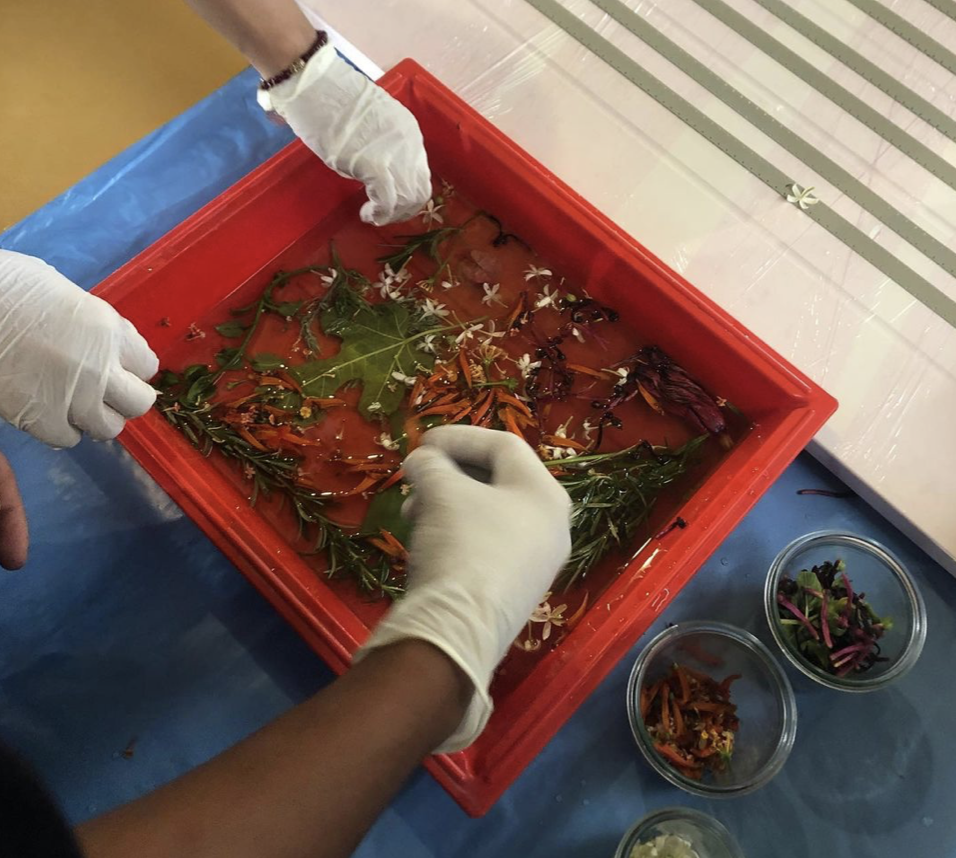

There is more than one way through which colonial influence is felt, exercised and imposed. One of them is denying a country’s cultural and historical impact and arguing about the coherence of its artistic voice. It presupposes the need for a fixed, linear narration. France’s obsession to revitalise Moroccan crafts to subjugate its population swirls in my brain uncomfortably. Art did not need external revitalisation, or help. Its existence was enough and plenty. It is currently enough and plenty. Whether based in Morocco, or part of its diaspora, Moroccan artists today explore their own rituals and memories, their ambiguous relationship to borders, oppression and national identity. They revisit crafts and traditions, oral art and the local politics of water and natural resources.

is a Moroccan and Swiss writer, artist and curator based in Brussels. She is interested in maintenance art practices and their relationships to North African Diasporas. Her research also revolves around non-linear and experimental ways of approaching archival records and histories. Through her practice “Postcards”, she explores ways to communicate her research interests in fragments.