Loio-Pérsio invitation to Stuttgart

After WWII, during the Wiederaufbau, there was a wish among progressive personalities in Germany to revive the Bauhaus spirit, which, as we know, had been locally interrupted by the pressure of the Nazi regime (one could argue that the spirit fled to other areas, though this won’t be the topic addressed here). Among some attempts of materialization of this wish count the Weißensee Academy of Art Berlin and the famous Hochschule für Gestaltung Ulm. Less mentioned or recalled in this context is the Staatliche Akademie der Bildenden Künste Stuttgart (ABK).

Two personalities are relevant in the history of that latter attempt: Herbert Hirche, described once as the “last Bauhäusler from Weißenhof” and Herta-Maria Witzemann, who, in 1952, both jointly succeeded Karl Wiehl as professors of interior architecture and furniture design in ABK. On a side note, Hirche himself earlier had worked at the Weißensee Academy of Art Berlin.

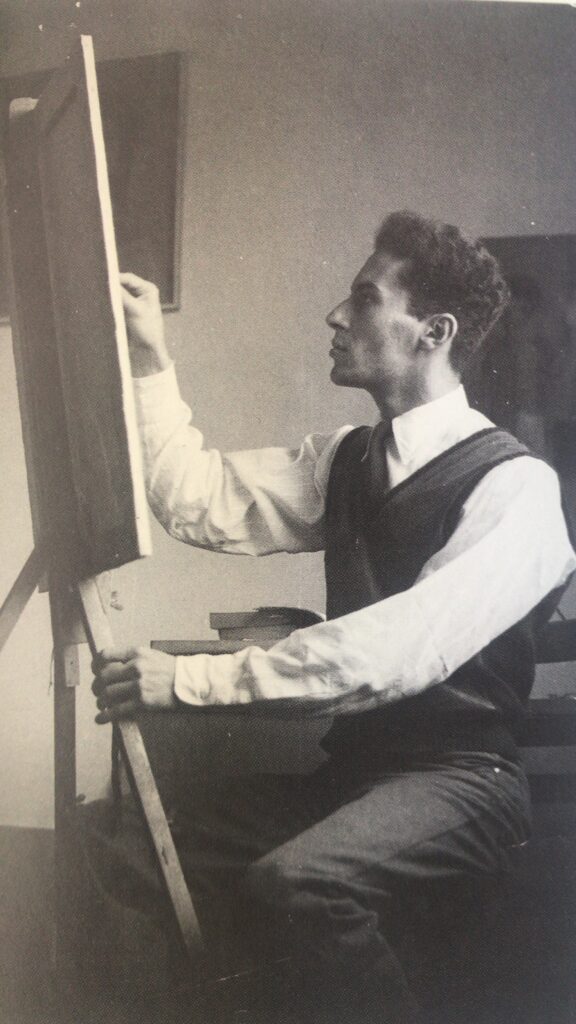

Stuttgart was an interesting cultural-intellectual environment in its own right. The German philosopher Max Bense, for example, had been working at the Technische Hochschule Stuttgart since 1949, becoming an associate professor a year later. He was a strong admirer and supporter of Brazilian concrete poetry and traveled to Brazil four times in the early 1960s. He has also organized exhibitions of Brazilian poetry and art in the university’s premises. Witzemann also traveled to Brazil around 1963, since she was very active internationally. It was there that she got to know Brazilian artist Loio-Pérsio, one of the pioneers of abstract art in Latin America, later inviting him to teach in ABK. In 1964 he stayed in Stuttgart for about a month, hosted by Bense, and considered the invitation, finally declining it. He believed that the language limitation would make something as complex as teaching painting and the subtleties of art doom to fail. And he probably foresaw homesickness.

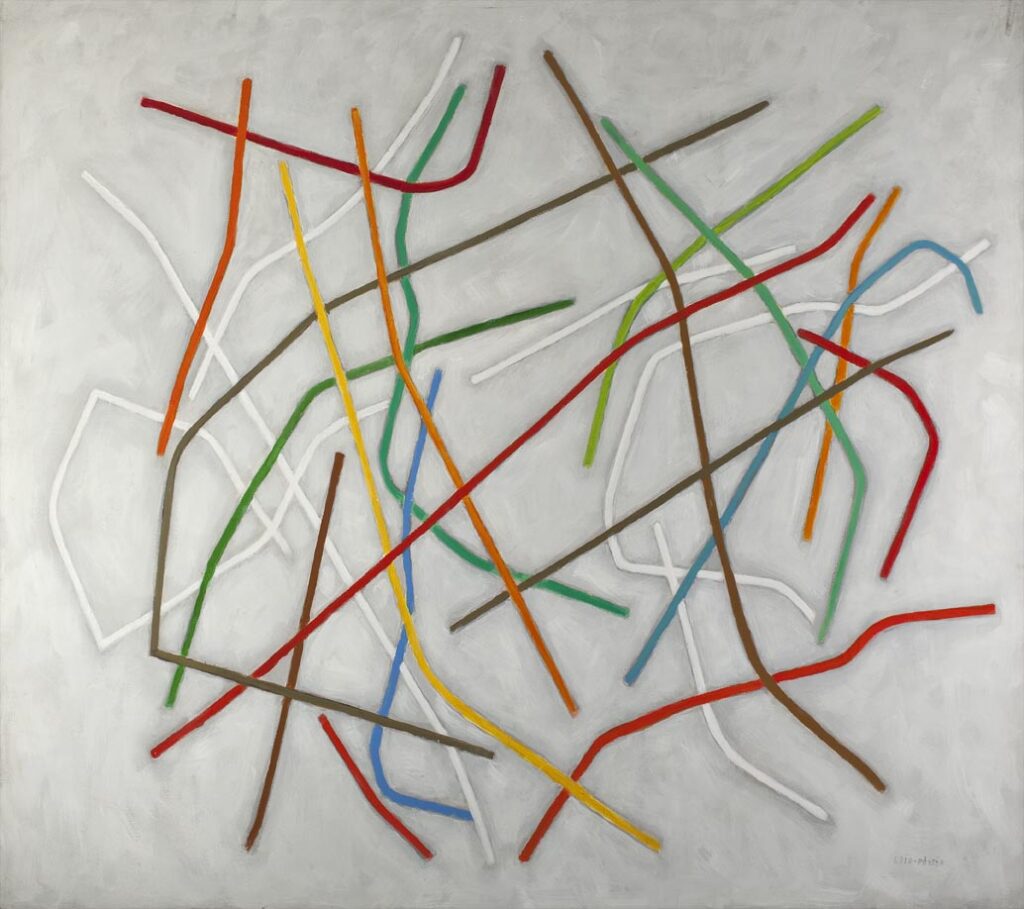

How are we to interpret Witzemann’s wish to have Loio-Pérsio on the faculty? She probably recognized in his art the qualities one sees in Kandinsky and Klee’s work. She probably saw him as a continuation of the Bauhaus spirit in the Americas. Which I believe is accurate. Somehow, her invitation broke a pattern, that of focusing solely on rationalistic approaches like concretism. Loio-Pérsio’s art represented the other avant-garde, informalism. And, in that respect, it is admirable that this didn’t prevent the friendship and exchange between Bense and Loio-Pérsio to happen.

is an artist-researcher and curator born in São Paulo, Brazil, based in Berlin, Germany. After completing a Masters in Arts in the Public Spheres at édhéa (Sierre, Switzerland) supported by the Wyss Foundation, his research and practice evolved from drawing and conceptual art to a broad reflection on decolonizing processes, democracy, writing and oral transmission strategies. Since 2020, he investigates the legacies of East-South cooperation during the Cold War years, and the lessons of modernism in Global South contexts (Guinea-Bissau, Tanzania, Brazil).